“The largest cache of documents found in the Cave of the Letters was the archive of Babatha, daughter of Shimeon son of Menahem. Thanks to this women – who managed to survive two husbands and must have spent most of her live in litigation, either suing the guardians of the fatherless son or being sued by the various members of her deceased husbands’ families – we have come by a priceless source for the period just preceding the war of Bar Kokhba. It is full of legal, historical, geographical, and linguistic data”

(Y. Yadin, Bar Kokhba, Weidenfeld&Nicolson 1971, p.222)

The discovery of ancient scrolls in the Judean Desert sparked a race between archaeologists and antiquity thieves to find additional fragments of the past to research or sell. Every nook and cranny in the caves and canyons of the Judean Desert was combed and excavated in the hunt for ancient treasures. Papyri and other documents yielded the best prices in the markets of Bethlehem, Hebron, and Jerusalem.

The first large Israeli archaeological expedition in the Judean Desert set out in 1960. In 1961, it members combed the cliffs of the canyons south of Ein Gedi. They divided into several teams; Yigael Yadin led the team that explored the cave in the Nahal Hever canyon that subsequently was dubbed the Cave of the Letters. Yadin’s team uncovered some of the expeditions most spectacular finds in this cave, where Jews from Ein Gedi had hidden from the Romans in 135 CE, during the final year of the ill-fated Bar Kokhba Revolt. The Roman army apparently besieged the caves in Nahal Hever until all those hiding in them died. In addition to the skeletons of the Jewish rebels, this cave contained letters from the time of Bar Kohkba that seem to have been part of an archive belonging to the leaders of the rebels in Ein Gedi. They include correspondence between them and Bar Kokhba’s headquarters at Herodium. Bar Kokhba himself signed those letters with the name, “Simeon son of Kosiba,” and the title, “nasi [president] of Israel.”

Babatha was widowed twice. Her first husband was Joshua son of Joseph and they had a son who also was named Joshua. After her husband’s death, Babatha waged a long legal battle with his family.

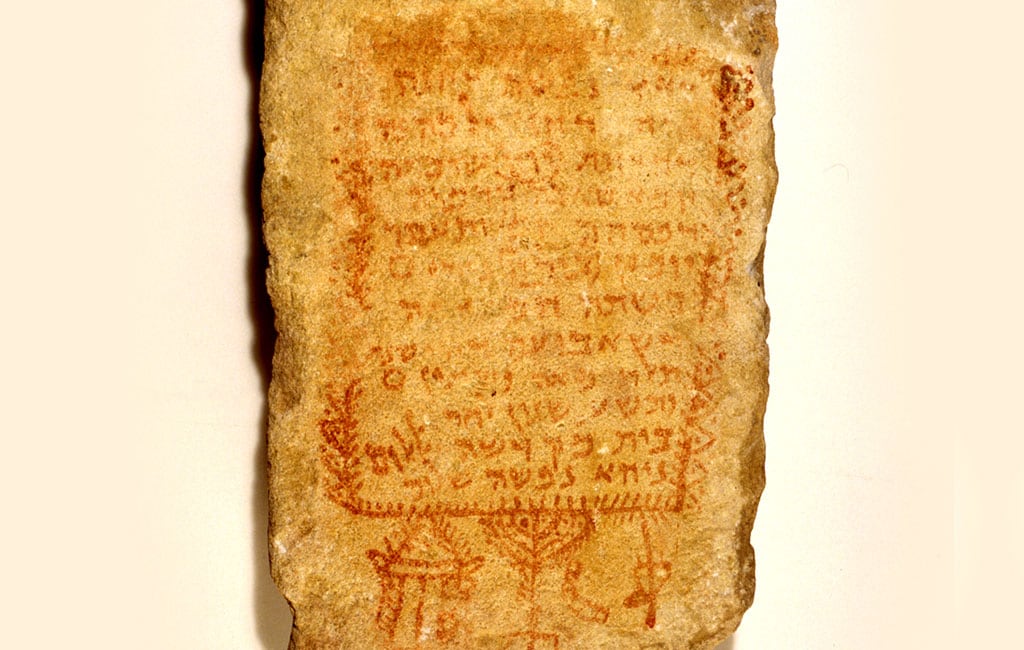

The excavation of the Cave of the Letters also found a leather purse with documents that had been hidden in the cave. It contained 35 papyri that were organized and catalogued by topic. They belonged to a wealthy Jewish woman who lived during the second century CE and was named Babatha the daughter of Simeon son of Menahem. These documents reveal more than a few details about Babatha’s life. She was born around 104 CE in Mahoza, a small agricultural town on the southeast shore of the Dead Sea near Zo’ar, a few kilometers from the border between the Roman provinces of Judea and the land of the Nabateans.

The archive sheds light on the personal life of a Jewish businesswoman, as revealed in the ketubah from her marriage to her second husband, Judah son of Eleazar of Ein Gedi.

Babatha was widowed twice. Her first husband was Joshua son of Joseph and they had a son who also was named Joshua. After her husband’s death, Babatha waged a long legal battle with his family regarding the custody of their son, child support arrangements, and the share of his estate due to her. Babatha remarried to Judah son of Eleazar, who was known as Kthousion, and served as her son’s guardian. Judah, a wealthy Ein Gedi resident and grove owner, also was married to Miriam daughter of Ba’ayan, with whom he had a daughter named Shelamzion.

Judah became ill and died in 130 CE, without having any children with Babatha. According to their marriage contract, she inherited his palm groves in Ein Gedi as collateral for his debts to her. In 135 CE, the last year of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, Babatha was at Ein Gedi. Perhaps she moved there when the revolt began or after she married Judah. His first wife, Miriam daughter of Ba’ayan, was the sister of Jonathan son of Ba’ayan, the leader of the revolt in Ein Gedi. When the Roman army arrived in 135 CE to destroy the Jewish settlements in the Dead Sea valley, the residents of Ein Gedi fled to hide in the caves that they had prepared for just this eventuality. Babatha set out with her son Joshua, Miriam, Shelamzion, and Jonathan for the large cave hidden in the cliff of the Nahal Hever Riverbed.

Esler’s main advantage in examining the text is that prior to becoming a historian, he was a lawyer. Since Babatha’s archive contains legal documents, he approached them not only from the perspective of a historian, but also of a legal scholar.

The Romans discovered their cave as well as the other caves in the Nahal Hever cliffs where rebels were hiding. They set up a camp on the top of the cliff on both sides of the riverbed. It is not clear if the Romans descended to the caves, which were accessed via a narrow stone ledge, or simply waited until the rebels died of thirst and hunger. In any case, none of the rebels in the caves survived. Yadin’s team discovered their skeletons in the caves in 1961.

Babatha apparently hid a waterskin containing the purse with documents, along with the keys to her home, a number of valuables, and cosmetic utensils in a cavity in the floor of the cave, where the excavation team found it.

Naturally, the correspondence between Bar Kokhba, from his base at Herodium, and his commanders in Ein Gedi, Jonathan and Masabala, was the discovery from this cave that won the most renown. However, Babatha’s archive, which reveals the details of the daily life of a Jewish businesswoman in the Dead Sea valley in the first century CE, attracted more than a little attention from researchers. Every detail of her life and those close to her, her property, and her legal struggles has been researched and written about in academic articles and books.

The papyri discovered in the Cave of the Letters include the marriage contract of Salome Komaise, daughter of Levy. Additional documents mentioning her were discovered later in Nahal Ze’elim, creating another personal archive of a woman from that period. Babatha and Salome lived in Mahoza, to the east of the Dead Sea. The archaeological finds indicate that they knew each other. The palm groves that they owned were next to one another, the same people served as witnesses to sign their documents, and they both died in the same cave in Nahal Hever. Beyond that, both women owned property, enjoyed a relatively high socioeconomic status, and managed complex businesses that involved large sums of money. Many people mentioned in both women’s documents were Jews, an indication that Mahoza was home to a flourishing Jewish community even though it was in Nabatean territory.

The material from their archives was published sluggishly, mainly appearing in the 1990s, some 30 years after it was discovered. Many researchers have studied the archives since then; their different interpretations of it have sparked stormy academic debates, which naturally inspired more articles and research.

The latest additions to the wealth of research on these archives were recently published. Prof. Philip Esler, of the University of Gloucestershire in England, examines the four oldest documents in Babatha’s archive in Babatha’s Orchard: The Yadin Papyri and an Ancient Jewish Family Tale Retold (Oxford University Press, 2017). Kimberley Czajkowski addresses legal aspects of life in the periphery of the Roman Empire, on the border between Judea and the land of the Nabateans, and how the residents coped with the political changes occurring around them in Localized Law: The Babatha and Salome Komaise Archives (Oxford University Press, 2017).

Mystery of the Four Documents

In 2013, Esler began reexamining the documents in Babatha’s archive. His area of expertise is the books of the New Testament, particularly the Gospel of Matthew, which was written in the second century CE. That sparked his interest in Babatha’s archive since it was written during the same period. Esler’s main advantage in examining the text is that prior to becoming a historian, he was a lawyer. Since Babatha’s archive contains legal documents, he approached them not only from the perspective of a historian, but also of a legal scholar.

Babatha’s contracts were preserved as “tied” deeds. The same text was written on the papyrus twice, at the top and the bottom. After the writing was completed, the upper part of the papyrus was rolled up and tied shut. The witnesses signed the back of the document next to the strings that sealed it in order to protect its integrity as an original document. If any doubts arose about the version of the text that remained visible on the unrolled section, it was possible to untie it in the presence of witnesses to see if the part in the rolled section matched it. If they matched, that meant the text had not been tampered with.

Four documents in the archive attracted Esler’s attention. They had been written between 94 and 99 CE, almost 40 years before the Bar Kokhba Revolt. They all dealt with agreements that were signed in Mahoza. One of them was a sales contract for the purchase of a large grove of date palms by Babatha’s father. This grove later was given to her and she was registered as its owner in 127 CE according to the Roman authorities. However, the other three documents are not related at all to Babatha’s father and two of them dealt with a matter that was not related to the grove Simeon bought or to his life in Mahoza.

’Amat-’Isi gave her husband two years to return the loan without interest. If the loan were not returned within that amount of time, they would need to pay interest of 9% per year and ’Amat-’Isi could demand to be repaid in full at any time.

The first of the three additional documents outlined the terms of a loan that two entrepreneurs, ‘Abad-‘Amanu and Muqimu, took to open an agricultural business in the profitable palm groves of the Dead Sea valley. Since they lacked the means to rent palm groves, Muqimu borrowed from the dowry of his wife ’Amat-’Isi. ‘Abad-‘Amanu and Muqimu were guarantors on the loan. This loan sheds light on the rights of women in the ancient world with regard to managing their financial assets independently of their husbands. Even though a married woman was able to loan property only to her husband, she was able to demand that the debt be repaid at any given moment in order to guarantee financial independence for her and her children, mainly as protection if her husband divorced her. The document on the loan, which was signed in 94 CE, features all the aspects of loans that are in use today on modern documents such as the length of time of the loan, the repayment schedule, the interest, the penalties in the case that the loan is not returned on schedule, and the names of the guarantors.

’Amat-’Isi gave her husband two years to return the loan without interest. The two entrepreneurs apparently thought that they would be able to return the loan within two years thanks to the profits they would earn from the groves. If the loan were not returned within two years, they would need to pay interest of 9% per year and ’Amat-’Isi could demand to be repaid in full at any time.

Esler did not understand what this agreement was doing in the purse with Babatha’s documents. He decided to study the four Nabatean documents about business dealings in Mahoza further in a bid to figure out what they were doing in Babatha’s archive.

The second document, which was signed five years after the first one in 99 CE, is a sales contract for a palm grove on the shore of the Dead Sea. A woman named ’Abi-‘adan daughter of ’Aptah son of Manigares sold it to a man named Archelaus. It was an expansive grove on the shore of the Dead Sea next to a grove that Nabatean King Rabel II owned.

Archelaus was a well-known figure in his day. He was a local who did well for himself, rising to a senior position in the service of the Nabatean royal family. His father, ‘Abad-‘Amanu, Muqimu’s partner, also served the Nabatean royal family in the army. Upon completing his army service, he returned to the village of his birth, invested in agriculture, and together with Muqimu began to expand the business by renting additional palm groves. He apparently helped his son, who also wanted to serve in the royal service, by tapping his extensive connections in the army and friends who resided in the Nabatean capital of Petra. Shortly before acquiring the palm grove, Archelaus was appointed governor of one of the provinces of the Nabatean kingdom and decided to expand his family’s holdings along the southern coast of the Dead Sea by purchasing this handsome palm grove on its shores. He saw the fact that the grove bordered the royal family’s property as a great advantage that would allow him to become even closer to the king and advance himself further.

The sales contract, as one would expect, detailed the exact borders of the grove that ’Abi-‘adan sold to Archelaus. Surprisingly, the third document in this group in Babatha’s archive, which was dated to one month after the palm grove was sold to Archelaus, is a sales contract for the same grove, with a few changes in the borders, to Simeon the son of Menahem, that is, to Babatha’s father. This raises the question of why and how did ’Abi-‘adan sell the same grove to two different people, one month after the other. The consensus among researchers is that the sale to Archelaus fell through so she sold it to Babatha’s father instead.

Esler rejected that interpretation. His close examination of the documents revealed a different story.

Simeon, Esler conjectured, wanted to buy ’Abi-‘adan’s handsome palm grove on the shore of the Dead Sea alongside the property of King Rabel II. However, when he approached her about purchasing it, he discovered that it already had been sold to Archelaus of the village of Rummon in exchange for 112 selas, which were equal to 448 Roman dinars.

Esler concluded that in the short time that passed between Archelaus’s purchase of the grove and its sale to Simeon, a number of dramatic events occurred. Archelaus’s father ‘Abad-‘Amanu apparently died suddenly and unexpectedly around the time of the sale. ‘Abad-‘Amanu, as mentioned above, was Muqimu’s partner and the two had taken a loan from ‘Abad-‘Amanu’s wife five years before the agreement between Archelaus and ’Abi-‘adan. Their agriculture venture apparently did not go well and they did not succeed to return the loan within two years, as they had hoped, and so they now needed to pay interest for three years in addition to the loan itself. The death of one of the partners and the failure of their business venture scared ’Amat-’Isi and she demanded repayment, in accordance with both the law and the loan contract.

However, ’Amat-’Isi did not turn to her husband since she knew that he was unable to repay the debt. Instead, she turned to Archelaus, the heir of her husband’s late partner. His closeness to the ruling family led people in the Zo’ar area to assume that he would have access to sources of revenue that would allow him to raise the money.

However, it turned out that Archelaus was unable to repay his father’s debt and so he asked ’Abi-‘adan to annul his purchase of the orchard so that he could get his money back and use it to pay at least part of his father’s growing debts.

Zo’ar was a small place and the gossip about the cancellation of the sale reached Simeon’s ears. However, he did not return to ’Abi-‘adan, but instead waited for her to approach him.

The Nabateans barely left any written history. All that is known about them is derived from a small number of Greek and Roman historians who described the Nabateans’ lifestyle in general based on secondary sources.

This is where the fourth document in the group comes in. This document also explains why the borders of the grove changed. The grove that Simeon wished to purchase was divided into two parts: a large section that ’Abi-‘adan owned and sold to Archelaus; and a smaller section that was sold to her husband Hasmar’il. Simeon wanted to buy the entire grove, since it was a wonderful, flourishing garden on the shore of the Dead Sea. As the only buyer remaining in the picture, he conditioned his purchase on it including both parts of the grove.

As a result, in one session, in the presence of five witnesses and stakeholders, both contracts were signed together. In order to ensure that Archelaus and his heirs would not claim one day that they actually bought the grove, Simeon had Archelaus serve as one of the witnesses on the contract for his purchase of the grove.

All of these documents were handed over to the main party of interest, Simeon. Since he held the original contracts, no one could claim that the sale had not been carried out in accordance with the law. The first contract, the loan that initially did not seem to be related in which Muqimu borrowed money from his wife, also became part of Babatha’s archive as proof of what led Archelaus to change his mind about the grove that he had purchased only a month earlier.

The drama surrounding this real estate transaction, that occurred 2,000 years ago, reveals the significance of women in the financial world in those days. The web of contracts was set in motion by the loan that a woman gave to her husband for business purposes. The woman did not only demand the repayment of the debts, but also protected her husband’s reputation and tried to find creative solutions to guarantee the continued success of her investments.

Babatha would go on to expand her personal property greatly. In addition to the large palm grove that her father gave her as a present and that she registered under her name in 127 CE, she also inherited a great deal of property in the Ein Gedi groves from her second husband. She went to Ein Gedi in order to manage her property and the legal discussions regarding it. She brought along the case with the documents – certificates, contracts, and marriage contracts that demonstrate the chain of legal events in her life. They were catalogued by topic, with the documents for each topic folded together into a bundle in the case.

She apparently was forced, against her will, to flee to the cave, but intended to return afterwards to continue her life. This is why she took along the documents and the keys to her house. At an especially difficult moment, she hid everything under a stone in a cavity in the rock, where they waited for 1,900 years until Yadin’s team found them.

The Death of Rabel II

Czajkowski’s book looks at how the residents of the area on the border of Judea and the land of the Nabateans handled the political upheavals that roiled their surroundings. The documents in both archives date from a very stormy period in this part of the Roman empire. The earliest documents are from 92 CE and the latest documents are from 132 CE. This period includes the reign of the last Nabatean king, Rabel II, and the annexation of the Nabatean kingdom into the Roman Empire by Trajan in 106 CE.

The Nabateans barely left any written history. All that is known about them is derived from a small number of Greek and Roman historians who described the Nabateans’ lifestyle in general based on secondary sources. Other than that, Josephus Flavius writes about ties between the Nabateans and the Hasmonean kingdom and Herod. Archaeological excavations of their cities and settlements revealed additional information.

The Nabateans’ origins are shrouded in mystery. They already had established themselves in the Arabian peninsula, southern Jordan, the Negev, and around the Dead Sea by the Persian period. They were a few nomadic tribes who spoke a strain of Arabic. For a long period, they were merchants who carried spices and perfumes across the Arabian peninsula to the Mediterranean Sea via camel caravans. They also traded in bitumen from the Dead Sea, which was used in medicine and embalming. Over time, they expanded northward and wandered throughout all of Transjordan up to the Hauran.

In the second century BCE, Greek sailors discovered the secrets of the monsoon winds that enable them to sail directly from India to the Red Sea, making the Nabatean caravan routes across land redundant. In the first century BCE, the flourishing Nabatean economy floundered. The solution was permanent settlements and desert agriculture. The Nabateans made the most of their hydrological skills to develop distinctive, wide-ranging desert agriculture, from producing wine to raising Arabian race horses for Greek and Roman circuses.

Petra developed as the kingdom’s capital and the seat of the Nabatean dynasty, growing into a large, flourishing city. Apparently the transformation from nomadism to agriculture led to the rise of a royal family. The first Nabtean king that is known is Aretas I, whose reign began around 168 BCE, and the last is Rabel II, who died in 106 CE. In other words, a royal dynasty continued for some 300 years. Rabel II became king in 70 or 71 CE, around the time that the Romans destroyed Jerusalem following the Great Revolt. Rabel II was a vassal king who ruled under Roman sponsorship, but maintained a degree of independence; this apparently was the case in the Nabatean kingdom since the time of Pompey.

When Rabel II died in 106 CE, the Romans annexed his kingdom to their empire. The new province was called Arabica. It is not clear how the annexation came about and whether it involved a battle or occurred quietly. However, it is clear that it caused a dramatic change in the lifestyle of the residents of the land of the Nabateans as new laws and new customs were imposed on them.

There is no doubt that this is one of the reasons that the documents in the archives of Babatha and Salome are written in the three languages used by the three regimes that prevailed in the Mahoza area. In her book, Czajkowski examines how the residents adapted their daily routines to cope with the changing legal system. Much of the book is dedicated to the scribes who draft the various documents. She provides an entire discussion on whether Babatha, Salome, and their households knew how to read and write. This is a complex question. One document in Babatha’s archive indicates that she did not know how to read, but that might mean that she did not know how to read Greek, Nabatean, or Aramaic, but did know how to read in another language. Some researchers claim that the use of scribes to write contracts indicates that the population did not know how to write. However, that claim seems slightly misleading since even in modern times when literacy is widespread, the average person does not write a sales contract, a loan contract, or even a simple receipt, but instead turns to a lawyer. There is no doubt that in a world in which three languages were employed, representing three legal systems and resulting from significant changes in rule, drafting a contract is not a trivial matter, especially since it would need to be valid in all three systems and perhaps in a new unexpected one. That made it vital to turn to a knowledgeable lawyer, or a scribe to use the language of the day, who was fluent in Aramaic, Hebrew, and Nabatean, as well as Greek and perhaps also Latin, to formulate agreements. This was particularly important for marriages, loans, and real-estate transactions, which remain in force for the long term, so that the documentation of them would be considered valid in a court in the future if needed, even if the regime changed again.

These documents date to a fascinating chapter in the history of the Jewish people: the period between the devastating destruction of the kingdom in the Great Revolt against the Romans and the total annihilation that followed the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Life for the average person continued amid these major historic events. People married, families grew, legal struggles were waged over property and inheritances, loans were extended, and agricultural ventures yielded handsome profits. Babatha and Salome were born some three decades after the Great Revolt. Their families may have settled in Mahoza in the years immediately after the revolt. They came of age in the midst of the preparations for the Bar Kokhba Revolt and continued to manage their legal affairs even after the revolt began, in between the battles. Their documents contain no mention of the revolt, they did business with both Jews and non-Jews, and their archives contain very little that is overtly Jewish or religious in nature. It is impossible to know what they were thinking in their final moments, in the cave in Nahal Hever, as the Roman Army camped above them waiting for them to starve to death or die of thirst. In those final moments in the cave, they most likely were not thinking about their flourishing palm groves, but about what whether all this extremism would give birth to anything other than destruction and devastation.