Legend has it that Noah’s son Japheth founded Jaffa. While that cannot be proven, there is no doubt about the antiquity of this port city, which appears not only in the Bible, but also in the annals of the pharaohs of Egypt and Greek mythology. Hasmoneans, Romans, Crusaders, Turks, French, and British fought over it, each leaving their own mark on the city.

Early Christian pilgrimage literature describes Jaffa as the city that Noah’s son Japheth established after the flood and cite that as the source of its name and the name of its main thoroughfare (Yefet Street). Other sources claim the name stems from the Hebrew word for beautiful (yaffeh).

Long before the Christians arrived on the scene, pharaoh Thutmose III listed Jaffa among the cities he captured in his campaign against the Canaanite kings in 1478 BCE. He conquered the city with a ruse similar to the famous trick behind the fall of Troy. When the Egyptian army failed to force its way into Jaffa, it feigned a retreat and left 500 large wicker breadbaskets outside the city walls. The starving people of Jaffa carried the baskets into the city. When night fell, Egyptian soldiers who had hidden under the bread in the baskets emerged and opened the city gates to allow the rest of the army in.

The el-Amarna letters, the royal Egyptian archive from the time of Akhenaton, reveal that ties existed between Egypt and Jaffa in the fourteenth century BCE as well. The archive includes letters the king of Jaffa sent to the pharaoh.

This connection continued in the following century, judging by the monumental city gate bearing the name and title of Ramses II that excavations of the ancient tell of Jaffa revealed. Another interesting source from the time of Ramses II is the Papyrus Anastasi I, an ancient parchment that the British Museum acquired from a Greek antique dealer named Giovanni Anastasi. It contains a detailed account of a high-ranking Egyptian official’s journey from Egypt to Lebanon. The official stopped in Jaffa on the way and provided a report about the city over thirty-three centuries ago.

Despite the legend, the first time Jaffa is mentioned in the Bible is not in relation to the flood, but much later as a border marker for the tribe of Dan (Joshua 19:46). Hiram, king of Tyre, demonstrated his loyalty to king Solomon by sending his contribution towards the construction of the First Temple in Jerusalem, the cedars of Lebanon, via the Jaffa port (Chronicles II 2:16). The Book of Ezra relates that the cedars for the Second Temple followed the same route (3:7). The prophet Jonah also set sail from Jaffa for his fateful meeting with the whale. Sennacherib, the king of Assyria mentioned in the Bible, lists Jaffa as one of the cities he conquered during his military campaign in the year 701 BCE.

It is unclear who resided in and ruled Jaffa during this time. It could have been Phoenicians from Sidon who controlled the coast as far south as Jaffa or perhaps Philistines, who arrived in the vicinity in the thirteenth century BCE. In the fifth century BCE, the archaeological record indicates that Eshmunezer, king of Sidon, ruled Jaffa, at least according to an inscription on his memorial stone. The city seems to have remained in Phoenician hands for some time as a Canaanite inscription found in Jaffa documents the building of a temple there dedicated to the Sidonite god Ashmun. The Roman historian Pliny, writing in the first century CE, described Jaffa as a city of the Phoenicians.

The conquests of Alexander the Great, in the fourth century BCE, rearranged the population and kingdoms along the coast. Alexander’s troops captured Jaffa in 333 BCE, on the way to conquering Egypt, and Greek colonists soon settled in the city, calling it Ioppe in honor of the mythological daughter of Aeolus, god of the winds. Also known as Cassiopeia, she was famous for her beauty and was the consort of Cepheus, king of Ethiopia. Jaffa and Cassiopeia are the central figures in one of the most famous of ancient Greek myths. Cassiopeia, according to one of the many versions, proclaimed her beauty to be greater than that of the Nereids, the daughters of the sea god, Nereus, and the consorts of the sea god, Poseidon. The Nereids’ complaint prompted Poseidon to send a sea monster to ravage the shores of Ethiopia. In desperation, Cepheus turned to the oracle of Delphi for help. The only way to placate the sea god, the oracle proclaimed, was to tie his and Cassiopeia’s beautiful daughter Andromeda to the rocks in front of the harbor of Jaffa as an offering to the monster.

Accepting this as her fate, Andromeda was chained, naked, to the rocks off the coast. Before any harm befell her, Perseus caught sight of her while flying, on his winged horse Pegasus, above the city on his return from slaughtering the gorgon Medusa. He quickly approached Cassiopeia and Cepheus and struck a deal with them: if he slayed the sea monster before it killed Andromeda, they would give him her hand in marriage. Perseus defeated the monster and returned to Ethiopia with Andromeda to plan the wedding. However, the princess had been betrothed to her uncle Phineus, who asserted his right to marry Andromeda.

A battle ensued. Cepheus and Cassiopeia sided with Phineus. Outnumbered, Perseus understood that he had no choice but to slay his challengers and used Medusa’s head to do so. Following their deaths, Poseidon placed Cepheus and Cassiopeia among the stars, hanging Cassiopeia upside down as punishment for her vanity.

Perseus then wed Andromeda. Their seven children became the rulers of Mycenae. One of their descendants was the Greek hero Hercules.

There are countless versions of this legend. It has inspired many works of art over the ages, and a number of movies, as well as speculation over which of the many large rocks at the entrance to Jaffa harbor was Andromeda’s rock.

Peter’s Vision

After Alexander’s death, his generals split the huge empire he had created. Jaffa became part of the inheritance of Ptolemy and the Ptolemaic empire that he founded in Alexandria. The next two centuries were rife with battles between the Ptolemaic empire centered in Egypt and the Seleucid Empire based in Syria. The latter eventually gained control over Palestine. In the second century BCE, the Seleucids weakened and succumbed to the growing power of Rome, enabling the Jewish Hasmonean kingdom to develop as an independent entity. At the time, Jaffa was an affluent Greek port city and its people did not view these developments favorably. Both the Jewish historian Josephus Flavius and the Book of Maccabees recount that Jaffa’s Jewish population was massacred by its Greek neighbors. In retaliation, Judah Maccabee attacked the city in 160 BCE, but was not able to gain control of it. Thirteen years later, Judah’s brother Jonathan launched another attempt to capture the city. The frightened population opened the city gates to the Jewish forces, but again the Hasmoneans did not manage to remain in control of Jaffa. Finally in 143 BCE, Simon, the third of the Maccabee brothers, captured Jaffa and turned it into the Hasmonean kingdom’s outlet to the sea.

Jaffa remained in Jewish hands for 106 years, until 37 BCE, when Pompey and the legions of Rome conquered it. A large Jewish community of seafarers and merchants remained in the city after the conquest.

A Talmudic tale relates that during the reign of Herod the Great, in the first century BCE, Nicanor, a wealthy Jew from Alexandria, had two huge copper gates made in his hometown for the Second Temple in Jerusalem and sent them there via the Jaffa port. A storm broke out while the ship carrying the gates was at sea, leading the sailors to throw one of the gates into the ocean to lighten the ship’s load. They were about to cast the second gate overboard when Nicanor stepped between the sailors and the gate, insisting that they throw him into the water before the gate. Nicanor’s dedication was rewarded by the immediate abatement of the storm. Furthermore, when the ship docked in Jaffa, the discarded gate miraculously washed up on the shore.

This story, which inspired the name of Jaffa’s The Gates of Nicanor Street, may have some basis in reality. According to Josephus and the Talmud, the outer gate of the Second Temple was known as the Gate of Nicanor. In 1902, a sarcophagus was discovered in Jerusalem with the inscription: “The remains of the children of Nicanor of Alexandria who made the gates.”

Christian sources also mention Jaffa, assigning it a key role in the development of Christianity. The Book of Jonah inspired the concept of the “sign of Jonah,” a sign that Jesus gave in Jerusalem as testimony to his divine mission. Furthermore, just as the biblical prophet Jonah passed through Jaffa, the Christian apostle Simon, the son of Jonah who became known as Peter, visited Jaffa. The New Testament relates that the faithful invited Peter to Jaffa after Tabitha, a god-fearing young girl, died. Peter entered her chamber, asked the mourners gathered there to leave, and “kneeled down, and prayed; and turning him to the body said, Tabitha, arise. And she opened her eyes: and when she saw Peter, she sat up. And he gave her his hand, and lifted her up, and when he had called the saints and widows, presented her alive. And it was known throughout all Joppa; and many believed in the Lord” (Acts 9:40-42).

Peter “tarried many days” (Acts 9:43) in Jaffa, staying at the home of another Simon, Simon the Tanner. There are a variety of traditions about where exactly in Jaffa Simon’s house was located; the Armenian church believes it was on the street in the Old City today known as Simon the Tanner Street, Catholics believe it was where St. Peter’s Church stands today, and the Russian-Orthodox church believes it was in the Orthodox church of Saint Peter near Jaffa in Abu Kabir.

While in Jaffa, messengers arrived from a Roman officer stationed at Caesarea, inviting Peter to visit him. The Roman officer, Cornelius, a god-fearing man, had a vision telling him to summon Peter. At that time, however, Jews did not stay in non-Jews’ homes because of the dietary laws, which created a dilemma for Peter over whether to accept the invitation. The Book of Acts describes the vision that shaped his decision: “Peter went up upon the housetop to pray about the sixth hour: And he became very hungry, and would have eaten: but while they made ready, he fell into a trance, and saw heaven opened, and a certain vessel descending upon him, as if it had been a great sheet knit at the four corners, and let down to the earth: Wherein were all manner of four footed beasts of the earth, and wild beasts, and creeping things, and fowls of the air. And there came a voice to him, Rise, Peter; kill, and eat. But Peter said, Not so, Lord; for I have never eaten anything that is common or unclean. And the voice spake unto him again the second time. What God hath cleansed, call not common. This was done thrice: and the vessel was received up again into heaven” (Acts 10:9-16). The message was clear and Peter made his way to Cornelius’ house. This opened the doors for non-Jews to join the church.

The Christian era came to an end in Jaffa in 638 CE, with the Muslim conquest. The new regime established a new regional capital in Ramle and Jaffa’s proximity to Ramle made it a significant port. However, when the power of the Muslim Umayyad dynasty waned and the Abbasid dynasty arose in its stead, the new rulers moved the main capital of the Islamic world from Damascus to Baghdad, turning Palestine and its surroundings into a remote province of the empire.

Crusaders, Mamelukes, and Turks

In the spring of 1099 CE, the knights of the First Crusade advanced along the coastal plain on their campaign to wrest Jerusalem and the holy land from the Muslims. After capturing Caesarea, the Crusaders turned inland and camped near Ramle, inspiring fear in the Muslim population. The residents of Ramle and Jaffa fled and a small Crusader garrison occupied the cities to control the route linking Jerusalem to the sea.

The first Crusader kingdom lasted for 88 years, until the fateful battle in 1187 at the Horns of Hattin, where Saladin defeated and destroyed the Crusader army.

A third crusade, led by Richard the Lionheart, king of England, and Philip II, king of France, set out from Europe to recapture Jerusalem from the Muslims. The Crusaders managed to regain a foothold along the coast and take Jaffa, but failed to gain control of Jerusalem. The capital of the new Crusader kingdom was set up in Acre instead.

Richard had left his brother John to rule in his stead while he led the Third Crusade. However, when word of his brother’s misconduct reached him, he prepared to return to England. He met with Saladin in Ramle to sign a peace treaty that delineated the borders of the second Crusader kingdom. Jaffa became the southernmost town of the new kingdom and was reinforced with massive walls and fortifications. Archaeologists have discovered inscriptions in Jaffa that report on the fortifications set up by German emperor Fredrick II. Louis IX of France also contributed fortifications, as well as churches and monasteries.

The days of the second Crusader kingdom were numbered. After Baybars led his fellow Mamelukes, a caste of Egyptian warrior slaves, to victory over the Mongol hordes in the Harod Valley in 1260, he became the new sultan of the Mamluke Empire. Baybars focused his attentions on eliminating the Crusader kingdom. Jaffa fell in 1268. The Christian population of the town was massacred and Jaffa was razed to the ground. All that remained was a small, sparsely populated village on the hill overlooking the small anchorage between the rocks.

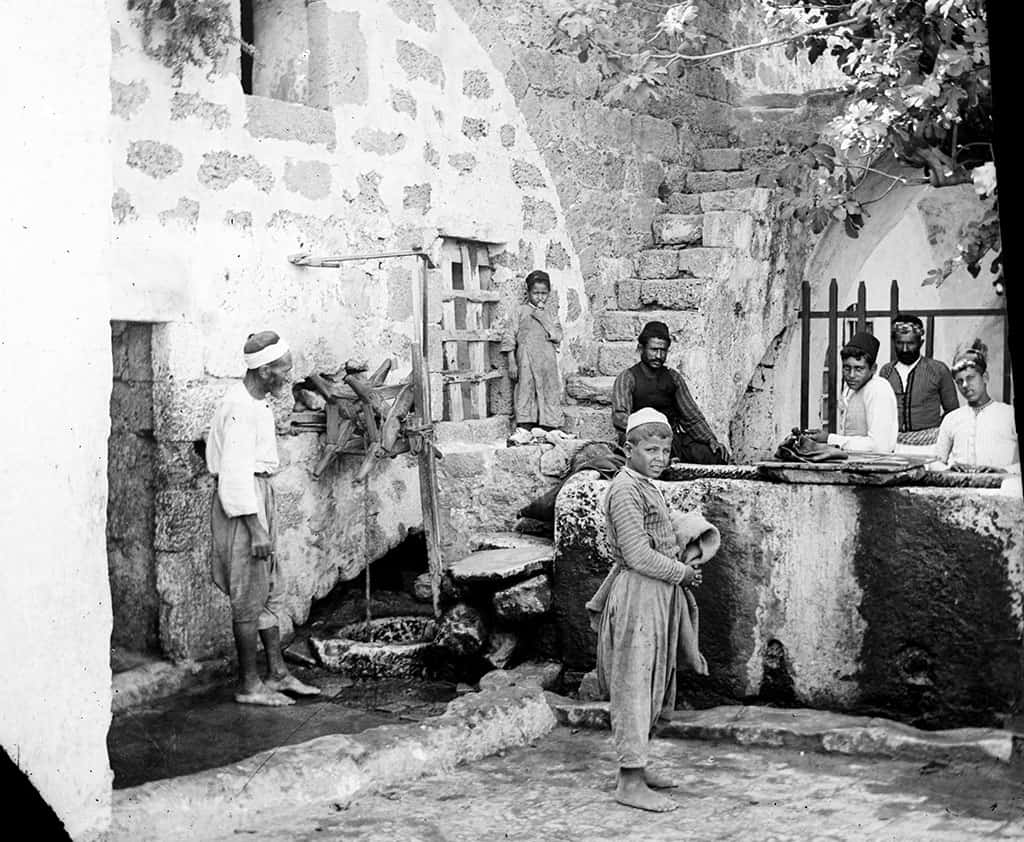

The Mamelukes systematically destroyed the cities along the coast so that the Crusaders would not be able to use them as a beachhead. In 1516, when the Ottoman army passed through Jaffa on the way to capturing Egypt, it was reported that the city was unoccupied. The few Christian pilgrims who landed in Jaffa on their way to Jerusalem in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, described the place as a ruin with one or two guard towers and caves in which pilgrims used to huddle in fear, while waiting for a caravan to take them to Jerusalem.

In the eighteenth century, the number of pilgrims arriving in Jaffa grew steadily as did the frequency of Christian pirate raids on the coastal plain. The Ottoman authorities responded by fortifying some of the coastal settlements. In 1703, they built two large towers at the entrance of the Jaffa harbor and garrisoned Ottoman soldiers in it. The improved security measures brought an influx of new settlers to the area. By 1763, Jaffa could boast 400 houses. This growth attracted the attention of Galilee strongman, Daher el-Omar, who occupied the city in 1773. Two years later, the Ottoman governor of Egypt, Muhammad Bey Abu Dhahab, besieged Jaffa and massacred its population.

The Modern Era

In February 1799, after conquering Egypt, Napoleon Bonaparte set his sights on the holy land. His forces crossed the Sinai Peninsula, seized control of Ramle, and on March 3, 1799, set up camp in front of the walls of Jaffa. Three days later, the French army launched its attack on the city. At 4 p.m., Napoleon’s soldiers breached the wall and stormed into Jaffa, where the local garrison engaged them in a fierce battle. Fighting raged from house to house, claiming the lives of hundreds of Ottoman troops. After the battle ceased, the French massacred the surviving inhabitants.

The next day, an epidemic of Bubonic plague broke out in Jaffa, infecting some of the French troops. Napoleon left the wounded and sick soldiers behind in the Armenian monastery in Jaffa and continued his march northward to Acre. Even though Napoleon successfully fought some of his most dazzling battles in the following weeks, Jazzar Pasha, the octogenarian Ottoman governor of Acre, with the aid of the British fleet, stemmed Napoleon’s tide of success. Napoleon was forced to retreat to Egypt. When he passed through Jaffa in the midst of the retreat, he ordered that the wounded and sick soldiers there be poisoned. What happened next is unclear. The French military surgeon allegedly refused to follow his orders and so an Ottoman doctor who had been taken prisoner was entrusted with the gruesome task, which he probably did not carry out. British troops, fighting alongside the Ottoman Turks, who arrived in Jaffa a few days after Napoleon took flight, reported finding the wounded and sick still alive.

After Napoleon’s retreat, the new Turkish governor, Abu Marek, began rebuilding Jaffa. In 1807, Muhammud Abu Nabut was appointed to replace him. Cruel and ruthless, he not only rebuilt the city walls, but also added new wharfs to the harbor, a fort and fortifications, and Jaffa’s main mosque, the Mahmudiya, named in his honor. Nabut’s term in office lasted 11 years, until 1818, and he brought stability, security, and prosperity to Jaffa. The number of vessels calling at the harbor grew annually, together with the number of pilgrims and volume of cargo landing at the port.

In 1831, the ambitious governor of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, and his son, Ibrahim Pasha, seized control of Palestine. He settled families from Egypt in a series of agricultural communities around Jaffa and invited Jews from Turkey and North Africa to settle in Jaffa.

With English assistance, the Turks managed to evict the renegade governor in 1840. However, British aid came with a price; the Ottoman sultan was forced to open his territory to foreign influences. Jaffa subsequently became a center of activity for European powers, the main port of Palestine. With the discovery that the local thick-peeled orange has a long shelf life and can easily be exported, Jaffa turned into a booming center of expanding citrus groves, packing centers, and export warehouses dedicated to the world-famous Jaffa orange.

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 brought about another surge in shipping traffic to the Jaffa Port. In 1892, the railroad between Jaffa and Jerusalem began operating. Jaffa became the economic heart of Palestine and home to an expanding business community and a modern intelligentsia.

Economic prosperity aided the development of new neighborhoods outside the Old City walls. Ajami and Jabaliya rose to the south, Manshiye to the north, and Nuzha and Salame to the east. In the 1870s and 1880s, the walls of the Old City were demolished to accommodate the expanding population and enable additional construction.

The growing prosperity of Jaffa attracted new populations to the town: Christians from Lebanon and Malta; Muslims from Syria and Egypt; Jews from Europe, who were part of the first wave of immigration inspired by modern Zionism, together with Jews from North Africa; and various Christian European organizations that established churches, hospitals, and schools.

In the early 1850s, several Christian families from Germany and the United States founded a small settlement northeast of Jaffa, naming it Mount Hope. An American group from Philadelphia, led by Clorinda Minor, joined them. The members included Johann Adolf Grosssteinbeck, the grandfather of author John Steinbeck. In 1858, Arabs attacked the settlement, murdering the men, raping the women, and burning the buildings. In 1866, another group of Christian Americans followed the charismatic preacher George Jones Adams to the holy land, purchased property near Jaffa, and attempted to establish an agricultural community. This attempt too was unsuccessful and the group sold its land to the Templers, a group of German Christians who founded a series of successful agricultural settlements across the country that flourished until the British expelled the Templers, at the outbreak of World War II.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Jaffa become the center of Zionist settlement activities in Palestine. Hovevei Zion, B’nai B’rith, and the Zionist Organization all opened offices in Jaffa. The first Hebrew secondary school, the Herzliya Gymnasium, was established in 1905, the same year that the future mayor of Tel Aviv, Meir Dizengoff, established the Geulah Company to purchase real estate. In 1908, Arthur Ruppin opened the Zionist Organization’s Palestine Office on Jaffa’s main street. Earlier, in 1887, Jews from Jaffa built the first Jewish neighborhood outside the walls of the Old City, Neve Tzedek. Dozens of new Jewish communities followed. In 1909, the neighborhood of Ahuzzat Bayit was established; it eventually became Tel Aviv.

The Twentieth Century

On the eve of World War I, the Ottoman authorities appointed Hassan Bek governor of Jaffa. He led the efforts to transform Jaffa into a modern western city. Old alleyways were expanded and new roads constructed. The Jamal Pasha Boulevard was built together with a new mosque in the Manshiye neighborhood. When the war began, Bek expelled all Jaffa residents who were citizens of enemy states, including many Russian Jews.

The British captured the city in 1917. Under their stewardship, Jaffa became the largest Arab city in Palestine and the center of the Palestinian national movement. Its population grew from 32,000 on the eve of World War I to over 100,000 on the eve of the Israeli War of Independence in 1948. Meanwhile, the development, side by side, of a Jewish and Arab national movement, both with aspirations to the twice promised land, caused relations between Arabs, Jews, and British to deteriorate. The Arab riots in 1921 and 1929, in which many Jews were killed, led many of Jaffa’s Jewish residents to move to the new Jewish community of Tel Aviv. The riots ultimately brought about an official separation of Tel Aviv from Jaffa and its recognition as an independent municipal entity.

Tensions escalated further into the Arab revolt that began in 1936 and changed the face of both Jaffa and Tel Aviv. Striking Arab workers temporarily shut down the Jaffa Port, inspiring the Jews of Tel Aviv to build a new port of their own. In an attempt to bring the revolt to an end, the British bulldozed wide corridors through the narrow, old alleys in the heart of Jaffa’s Old City, so armored cars could access the innermost hideaways of the leaders of the revolt.

In 1947, the British turned the issue of the Palestine Mandate over to the United Nations. On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly voted to accept the United Nations’ Partition Plan for Palestine, which recommended the creation of independent Arab and Jewish states and a special international regime in the city of Jerusalem. Jaffa was to become an Arab enclave inside the Jewish state.

As hostilities between Jews and Arabs grew in late 1947, sniper attacks and gunfire intensified along the outskirts of the neighborhoods between Jaffa and Tel Aviv. The British tried to manage the conflict by erecting barricades manned with armed guards between the two cities, but to no avail.

In January 1948, the Lehi underground group, known in English as the Stern Gang, blew up the Saraya building, the Arab administrative headquarters in Jaffa. The blast claimed 21 lives. In April 1948, the Irgun (IZL), another Jewish underground group, set out to take over Manshiye, Jaffa’s northernmost neighborhood. The British intervened to prevent Jaffa from falling into Jewish hands. Even with British protection, Jaffa’s Arab residents feared for their safety. The ensuing weeks saw a mass exodus from Jaffa: by land to Ramle and Jerusalem, and by sea to Gaza and Lebanon.

On May 13, two days before the establishment of the State of Israel, the remaining leadership of Jaffa surrendered the city. The 3,600 remaining Arabs were concentrated in Ajami.

Following the establishment of the State of Israel, Jaffa filled with Jewish immigrants and its harbor became a major entry port for the hundreds of thousands of Jewish immigrants pouring into the country from Europe and the Arab world.

In 1950, Jaffa was officially reunited with Tel Aviv. A large part of the Old City was destroyed together with the entire Manshiye neighborhood. When a modern, new port opened in Ashdod, the old Jaffa port became redundant and only a handful of fishermen continued to use it.

In 1961, the Old Jaffa Development Corporation was established to renovate the Old City and turn it into an artists’ colony. Jaffa soon filled with galleries, nightclubs, restaurants, and souvenir shops. But as the years passed, the artists aged and demanded that the nightclubs close and the tourists stop disturbing the tranquility of the alleys under their studios. Entertainment moved to Tel Aviv, leaving Jaffa to deteriorate into poverty.

When Ron Huldai was elected mayor of Tel Aviv in 1998, he decided to make the development and restoration of Jaffa a priority, establishing the Governance of Jaffa to plan and implement the process.

In recent years, Jaffa has been changing. Like many old cities around the world, development of the inner core of the city attracts a more affluent population and causes real-estate prices to rise, making it difficult for the existing population to afford to live there. This process of gentrification is also happening, on a large scale, in Jaffa. Since the new affluent population is largely Jewish, while the existing population is predominantly Arab, political issues are added to the socioeconomic friction.

Jaffa remains one of the most fascinating places in Israel. Even though many of its ancient buildings have been destroyed, there is still much to be seen. The city has a long history, a myriad of architectural styles, and a wealth of trendy places to shop, eat, and barter while gaining new insight into the entwined history of the two peoples residing in this land.