Painting her mother’s Auschwitz tattooed identification number turned artist Rachel Nemesh’s work into a voyage of self-acceptance as a Second-Generation Holocaust survivor and an emotional deepening of relations between mother and daughter. The results of this voyage can be seen in the exhibition As One, at the Israeli Art Gallery in the Memorial Center in Kiryat Tivon

Assaf Kugler

Rachel Nemesh’s website contains all the usual categories: About; Pictures – with pictures of her work; Jewelry – displaying the results of years of her work before she became a painter; Contact us; and the Testimony of Katia Nemesh. This last category exhibits the photographed testimony with the photos that were transformed into drawings of Nemesh’s mother, Katia, a Holocaust survivor, recounting her experiences during the Holocaust. This surprising twining of professional site and personal family history, of testimony and memory, loss and regeneration, creativity, and mother and daughter relationship embedded in the website, come to their fulfillment in the exhibition “As One” recently opened in the Kiryat Tivon Israeli Art Gallery. The tattooed Auschwitz identification number on her mother’s hand appears again and again in the mother and daughter portraits.

I belong to the second generation of Holocaust survivors, and this defines me and has defined me for my entire life. It characterizes my behavior, my relations with others, with my mother, with my children—even my relation to art.

Rachel Nemesh was born to Katia and Dov, in Kiryat Tivon, a small town overlooking the Jezreel Valley. “I grew up on “the Hungarian Street,” where many of the olim from Transylvania and Hungary had settled. After finishing high school, I studied photography and took art classes at the Avni Institute of Art and Design in Tel Aviv, in plastic arts. Thirty years ago, I abandoned the field of plastic arts and opened a jewelry studio.

Eight years ago, Nemesh closed her studio and began to study painting with Eli Shamir. “From that day, I knew that I had to dedicate my life to painting.” Five years ago, she decided to paint a portrait of her mother. The painting would be the beginning of the current exhibition with profound realism in oil paintings portraying art that ties the two issues of Second-Generation Holocaust survivors, and the feminist look of the mother-daughter relationship.

The idea of turning the paintings into an exhibition about her mother was born after a visit by curator Michal Shachnai Ya’akobi. Shachnai was so impressed by the big oil paintings and immediately asked when a presentation could be ready.

The exhibition opened four years later, on March 5, 2020, and after just a week closed because of the COVID-19 outbreak. Nemesh’s mother, the central object of the exhibition, was locked down in her room in the old age home in Kiryat Tivon.

Katia Nemesh was born in Dej, (today in Romania). Her very religious parents owned a large textile shop. Most of the family, except Katia and one uncle, died in Auschwitz. She was released after the Death March from Bergen-Belsen, a very sick Musselman on the verge of death, and wandered about the streets begging for alms. Six months later, after recovering slightly, she decided to return to her hometown, Dej. There were no acquaintances left. The ransacked house of her well off family was full of holes and pits dug by the townsfolk looking for buried treasures. After meeting Dov, Rachel’s father, the two decided to make Aliyah. Their ship was caught by the British, and they landed in the Cyprus detention camps. Following the creation of the State of Israel, they settled with other olim from Transylvania in Kiryat Tivon.

In her youth, Katia had studied languages with a private teacher. She had been accepted for medical studies in the university, but the war put a stop to all that. In the camps in Cyprus, she began to study languages, and after making Aliyah finished her master’s degree in English and additional studies at Oxford University, England. Back in Kiryat Tivon, she became the town’s legendary English teacher.

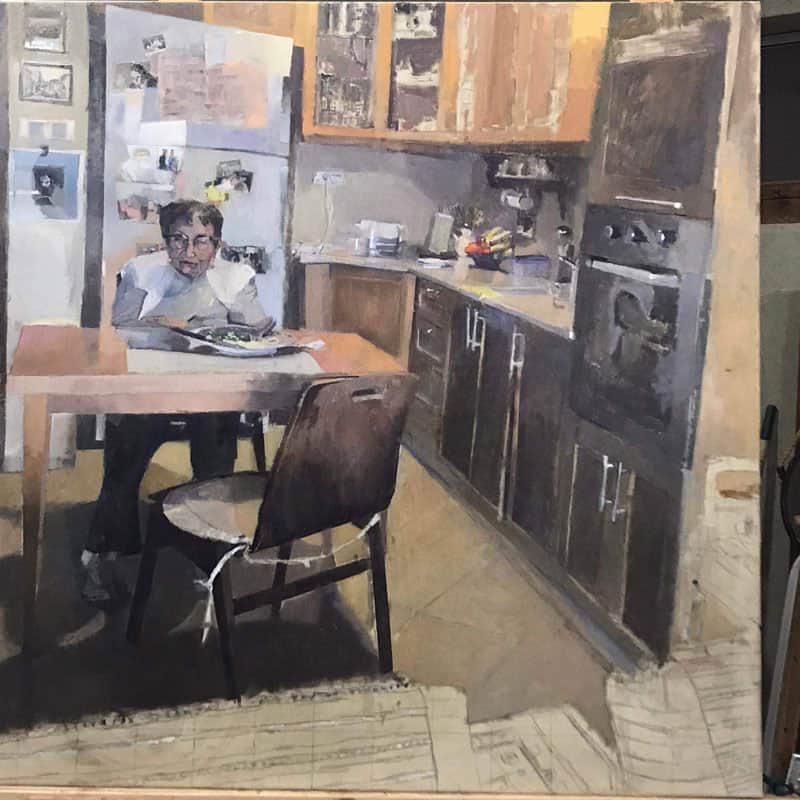

“Through her room that appears in the paintings, we can learn about her,” says Nemesh. “The utensils, the Hungarian embroidered runners, the neatly organized furniture, the portrait of a rabbi hanging on the wall, the books she loves, and the dictionaries attesting to her love of languages. She is very well educated and loves to read. The place where a person lives, his room and surroundings, reveal much about his personality.”

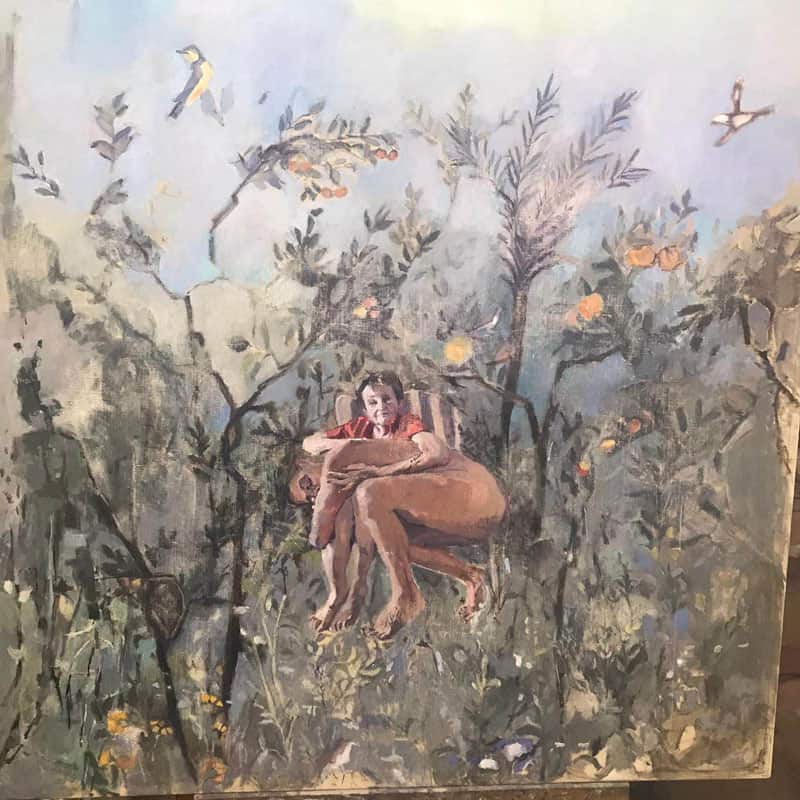

The exhibition shows two different characteristics of Nemesh’s mother. One part of the display shows the burden of old age on a woman secluded in her room, the other part exhibits large paintings that have an almost majestic feel, with the commanding figure of the mother looking down at the viewer. “For me, she is larger than life; she is a heroine with a strong will to survive, and at the same time, a small woman in an old age home. It is the story of each one of us – in the end, we are alone.”

When I started to talk about this with others, I opened up, created a place for memories, a place to embed the stories of our parents, of my mother. Slowly I noticed that I began to remember things she told me

In many of the paintings, the tattooed number appears in its actual place on Katia’s hand. However, in some of the pictures, it appears on Rachel’s body, or on an eagle, hovering over her mother, as if it is the wandering symbol of the story that they both share.

“I belong to the second generation of Holocaust survivors, and this defines me and has defined me for my entire life. It characterizes my behavior, my relations with others, with my mother, with my children—even my relation to art. I have never documented anything, never made an effort to finish things – until I realized that this was a kind of survival technique; We always have to move on, to continue on our journey. Because we are constantly on the move, keeping things, memories, relations, is a kind of luxury.”

Creating the exhibition allowed Nemesh to feel more comfortable with herself. She even joined a support group of second-generation survivors – something that she had never wanted to do before.

“When I started to talk about this with others, I opened up, created a place for memories, a place to embed the stories of our parents, of my mother. Slowly I noticed that I began to remember things she told me. Where she was during the war, what she did. Small details. My mother also noticed that I suddenly began to remember.

The paintings opened an opportunity for intimate work with the mother, even nude photographs, as a base for a portrait.

“The nude photos were taken by my husband Sharon, on his cellphone. I sat my mother down on our striped living room striped sofa, but nothing was staged. Going over the photos later, I could recognize the history of art, famous scenes such as La Pieta, or the resurrection. During the session, I felt something intimate that was not there before, that I never had with her. Something real. I realized that all my mother ever wanted was another hug from her mother, whom she had last seen in the line at Auschwitz.”

The meeting of Katia with her exhibition images was not comfortable. “It seemed as if she had to come out of hiding. But, at the opening event, she was honored and respected, and this made her feel good.”

The exhibition has now reopened at the Israeli Art Gallery, in Kiryat Tivon.

Sunday, Tuesday, 09.00-12.00

Thursdays between 10.00-18.00

Tel. 04-9835506.

As One, Rachel Nemesh.

Curator Michal Shachnai Ya’akobi.

Israeli Art Gallery, Kiryat Tivon

My English Teacher

The old photo of the three women and a man, sitting together in Kiryat Tivon, was taken during the years of austerity in the 1950s. Katia, Koti to her Hungarian friends, is on the right of my mother, Hanna Kohl, and Lutsi Diamenstein is to her left. The man on the far right is my late father, Emil Kohl.

Avgar Admati, a childhood friend of mine, describes how she loved Katia Nemesh, our English teacher, and how, at the same time, she was afraid of her. “She had a kind of respectful quiet that awed us. A powerful gaze and voice that motivated us to study. Katia, like my mother, loved languages – European languages that could take them to another place, away and over the sea.

They had gone through a lot, something that we will never be able to imagine. But, Katia, like my mother, needed to instill in us – the young generation growing up in the new country, a love for the things that they had left behind – far away from this harsh and dry land. They wanted to open for us that window on culture, art, and literature of a world that for them was gone forever.

Dita Kohl