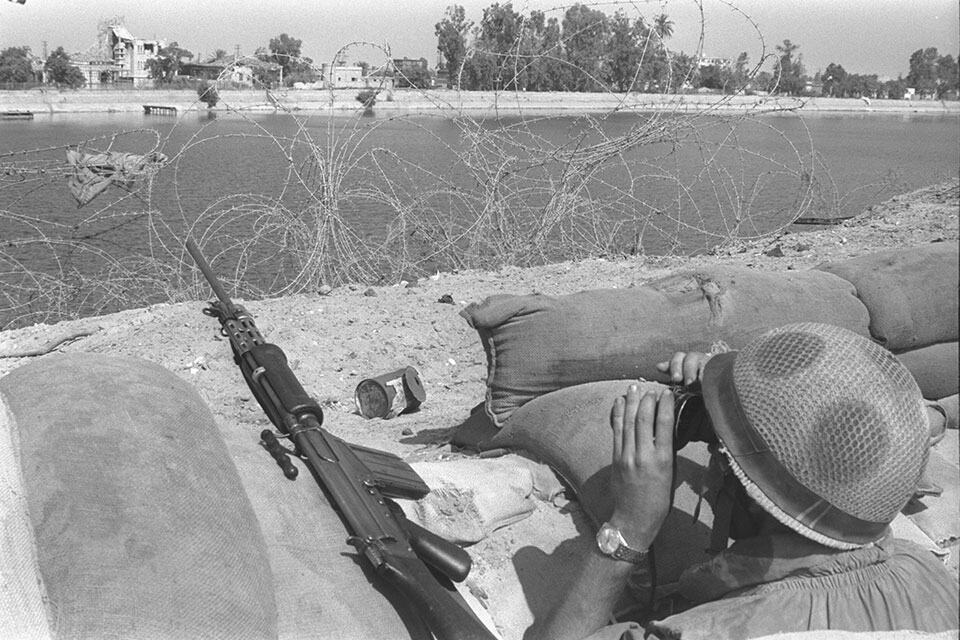

The Crusader siege of Acre has many conflicting accounts, Christian narratives as well as Muslim descriptions. Recently scholars are trying to create a unified account of the 653-day battle – the longest battle of the Middle Ages

As the sun rose over the mountains of Galilee and lit up the flat plain along the Mediterranean Sea, the army of Saladin, Sultan of Egypt and Syria, appeared before the walls of Acre. It was July 9, 1187; five days after the sultan had decimated the Crusader army at the Horns of Hattin. One thousand knights had died in the battle; many more were taken prisoner, including the Crusader King, Guy de Lusignan. The Holy Cross, brought from Jerusalem to instill courage in the Knights, had also fallen into the hands of the Muslims. Following his victory, nothing could stop Saladin from marching on Jerusalem, the capital of the Crusader Kingdom. Nevertheless, Saladin preferred to deal first with the Crusader coastal cities, to prevent the landing of Christian reinforcements from Europe.

The Crusader governor of Acre, who had managed to escape the carnage at the Horns of Hattin, hurriedly surrendered the city to the Muslims. Some of the nobles in Acre protested the decision and threatened to set fire to the city and commit suicide. However, once Saladin promised that the Christian population of Acre could peacefully leave the city and take their possessions with them, the nobles conceded. The Sultan appointed his cousin, Afdal Ali, as governor of Acre, and marched his army northward to the Crusader cities along the coast of Lebanon. Sidon fell on July 29, Beirut eight days later. Then he turned to the south and took Ashkelon. On October 9, 1187, the Sultan entered Jerusalem. The majority of the Christian population fled; those remaining were slaughtered. Jerusalem would remain in Muslim hands for the next 730 years.

The only Crusader city that held out was Tyre where many of the survivors of the Horns of Hattin had taken refuge. Ten days after the Crusader debacle the Marquis Conrad of Montferrat arrived at Tyre. He had left Constantinople a few days before the battle at the Horns of Hattin, to join his father in the Crusader camp. The battle was over before he managed to dock at Acre, and his father had fallen prisoner. Conrad made his way to Tyre and began to organize the city’s defense. He soon became the main Christian leader in the East.

Conrad saw himself as Guy de Lusignan’s rival for the title of King of Jerusalem. Guy had received the royal title due to his marriage to Sibylla, mother of the former king; Baldwin V. When Baldwin suddenly died, in 1186, at the age of nine, his mother, Sibylla, had chosen Guy as her spouse and by that made him King of Jerusalem. De Lusignan was Sibylla’s second husband. Her former husband, William of Montferrat, Conrad’s brother, had died in 1178. Conrad never forgave her for not taking him as her spouse.

The disaster at Hattin echoed around the Christian world, rekindling the waning spirit of the Crusades. Pope Urban III planned to declare a new Crusade to free the Holy City from the Muslims. However, his heart did not survive the awful news from the Holy Land. On October 20, 1187, he suddenly died. It fell to the new pope, Gregory VIII, to launch Christendom’s Third Crusade.

Three months after the pontifical announcement the only two leaders who could lead the crusade – Henry II of England and Phillip II of France, met in order to hear from the bishop of Tyre a firsthand account of how the Holy City had fallen. The horrific description moved the two royals and they declared on the spot that they would take up the cross. Henry created a special tax, “Saladin’s Tithe,” that raised the large sum of 12,000 pounds sterling, to support the crusade, paid mostly by the Jews of England. Two months later the German Emperor, Fredrick Barbarossa, announced that he too would join the crusade. However, while preparations were being made, Henry II died. The throne of England went to his third son, Richard, known as Richard the Lionhearted. On his coronation, Richard announced that England holds stay on its intention of going on the crusade.

As Europe got organized to save the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the kingdom’s nobles were busy squabbling among themselves. In the summer of 1188, Saladin added fuel to the local rivalry by releasing Guy de Lusignan from captivity. Saladin hoped that the struggle between Guy and Conrad for the leadership of the kingdom would weaken the resolve of the remaining knights and nobles.

On his release, Guy gave Saladin his word that he would not take up arms against the Muslims, a promise that no one expected him to keep. Guy made his way to Tripoli (Lebanon) where many of the nobles of his defunct kingdom had taken refuge.

Meanwhile,

Conrad had managed to fortify Tyre and repel an attack by Saladin in November

1188. After a ten-month siege, the sultan gave up and retreated to regroup in

the mountains.

In Tripoli Guy and Sibylla raised an army of 500 knights and 7,000-foot soldiers, most of them survivors of Hattin. Leaving Tripoli, this makeshift army marched down the coast, to Tyre. Conrad refused to let them into the city, and Guy decided to continue south, to the next coastal city, Acre.

News of this new Crusader army quickly reached Saladin, bivouacked in Lebanon, at the massive fortress of Beaufort overlooking the Litani River. The sultan’s commanders advised immediate attack. The sultan hesitated, thinking that the small army was actually a trap.

A four-day march brought Guy across the Ladder of Tyre, the steep mountain range between Lebanon and the Land of Israel, to the fertile valley of the Betzet River. The next day, August 27, 1189, Guy and Sibylla’s small Crusader force reached Tel Acre, the hill overlooking the city. Blocking access to the gates of the massive walls, they announced that Acre was now under siege. It was the beginning of the Crusader period’s longest siege.

Saladin still hesitated. Even though the Muslim garrison of Acre could have easily beaten off the handful of Crusaders on the hill, the Sultan decided to move his army to the coastal plain around Acre, and attack the Crusaders from the rear. On August 30, he took up positions on Tel Kisan, in the wide floodplain southeast of Acre, trapping the Crusaders between the garrison in the city and his forces on Tel Kisan.

The Crusaders managed to mount a few small sorties against the walls of Acre, but without siege engines, Guy had no chance of penetrating the massive fortifications. Meanwhile, the Muslims succeeded in opening a corridor through the Crusader lines and send reinforcements and supplies into the city.

Fortunately, for Guy de Lusignan and his small group of knights, two weeks after he took up positions opposite the walls of Acre, in the middle of September, the vanguard of the Third Crusade arrived; a fleet of 50 ships carrying 12,000 Flemish, German, and Breton troops. A few days before a small fleet of Danish and Welsh soldiers had arrived from Cornwall. At the end of September Conrad of Montferrat joined the siege, understanding that the opening gambit of the Third Crusader was going to be opposite the walls of Acre. Conrad arrived with a force of 20,000 soldiers and 1,000 knights. By the end of September, the Crusader army numbered more than two thousand knights and over 30,000 soldiers. A fleet of Christian ships blocked Acre from the sea and prevented any supplies from entering its harbor.

The Muslim forces inside the city were under the command of Emir Baha al-Din al-Asadi Karkush, one of Saladin’s most experienced commanders. The Muslim strategy was to organize simultaneous attacks on the Crusaders, from the direction of the city and the direction of Saladin’s troops on the plain. At the dawn of September 14, the Muslims launched their first attack, the first battle of the siege of Acre.

Saladin’s forces tried to reopen the corridor into the city and at the same time engage the entire Crusader army. The left side of the Muslim front advanced along the banks of the Na’aman River to the south of the city. The right flank advanced along the beach north of the city and in the center, Saladin’s best troops engaged the main Crusader army.

During the first day of the battle, the Muslims managed to reopen the narrow corridor to the city. On the second day, fresh Muslim troops widened the gap in the Crusader lines and set up a defensive perimeter along the corridor. Once the break in the Crusader front was established, Saladin sent supplies, food, and reinforcements into the city. The next day Saladin himself entered Acre and from the top of the walls looked out over the battlefield.

The Muslims tried to tempt the Crusaders to leave the safety of their batteries and launch an attack, but the Crusaders did not budge. Eventually, the Muslims managed to break through the batteries and reach the tents of the main Crusader camp. Only fierce hand-to-hand fighting managed to stop the attack.

Two weeks later, on October 4, the Crusaders were ready to counterattack. The battle began at 9 a.m. The Templar and Hospitaller knights charged into the lines of the Muslim soldiers. At a certain point, Taki al-Din, Saladin’s cousin, commanding the forces in the center, feigned a retreat to entice the Crusaders to advance further away from their defenses. Saladin, seeing the retreat from afar, thought that his center was collapsing and diverted troops in the direction of Taki al-Din. The Crusaders, noticing that Saladin had thinned out the troops in his area, charged in that direction. The Muslim force broke and retreated. At this point, when the knights could have won a decisive victory, they halted their advance to pillage the Muslim tents, losing the momentum of their attack.

Saladin regrouped his dispersed army and attacked the Crusaders busy pillaging the Muslim tents. The battle turned into a Crusader blood bath. The Crusaders, embroiled in the tents had no room to maneuver and fell one by one. The carnage stopped when Geoffrey de Lusignan, Guy’s brother, managed to put together a group of Knights and halt the Muslim attack.

Come autumn the European vessels began to leave. Sailing in the Mediterranean stopped during the winter, and new ships could only arrive in spring. On December 26 al-Adil, Saladin’s brother managed to enter Acre harbor with an Egyptian fleet from Alexandria. It was the last fleet to arrive before winter set in.

16 months of fighting had passed since Guy de Lusignan had first appeared before the walls of Acre. However, while most of Saladin’s troops returned home for the winter, the Crusaders had nowhere to go. They stayed in their trenches and tents, facing the cold, rain, and a growing shortage of food.

Enter

the Kings

During the winter very little fighting took place, and Saladin, ill in bed, utilized the lull to regain his strength.

The Crusaders utilized the winter to build a new array of trenches and batteries and construct impressive siege machines, including three large wooden towers higher than the walls of Acre. The battle resumed at the end of March 1190. Conrad, who had spent the winter in Tyre, sent fresh troops and provisions, and Saladin regained his health and took command of his troops.

The fighting now concentrated on the defenders’ attempts to stop the advance of the Crusader towers toward the walls. By May 5, the Crusaders succeeded in positioning their towers, and the Acre garrison now concentrated their efforts on setting the towers on fire.

Meanwhile, Saladin received worrisome news on the advance of the army of the German Emperor Fredrick Barbarossa. The emperor had left Regensburg in southern Germany on May 11, 1189, with an army of 15,000 soldiers and hundreds of knights. The German army was the most disciplined and organized of any European army. The emperor planned to lead the bulk of the army overland to Acre, marching a disciplined 30 kilometers a day. Additional German units, sent by sea, had stopped over in Portugal to help the Christians fight the North African Moors. The maritime force wintered in Marseille and Sicily and arrived in Acre in June 1190.

Meanwhile, the main German army marched through the Balkans fighting all the way against Bulgarian brigands and Turkish marauders. At the beginning of June, the Germans captured Konya, in Anatolia. Then, while crossing a small river, Fredrick Barbarossa slipped from his horse and drowned. It was a serious blow. His son, Fredrick of Swabia, tried to take command but lacked the leadership qualities of his father. The army fell apart and became prey to ambushes and attacks. On June 21, 1190, the survivors of the grand army crawled into Christian Antioch, Syria. After two months of recovery, they continued to Tripoli where Conrad of Montferrat helped them get to Acre. Of the proud army that had set out 13 months ago, only 700 knights and several thousands of soldiers made it to Acre. The last blow occurred on January 20, 1191. Fredrick of Swabia fell ill and died. The German army as an organized fighting force ceased to exist.

In July 1190, Sibylla, Queen of Jerusalem, passed away. Her death undermined the legal status of Guy de Lusignan as king of Jerusalem. On October 24, Conrad married the new heir to the title, Sibylla’s half-sister, Isabella. The three archbishops in the Acre camp opposed the marriage. For starters, Conrad was already married, to two other women, one in Italy and the other in Constantinople. Isabella was also married – to Humphrey III of Toron, a member of one of the noble families of the Crusader kingdom. Humphrey and Isabella had married when Isabella was 11 years old. Following the death of Sibylla, Humphrey, who was present in the Crusader camp, did not try to claim his right to the throne, and Conrad took advantage of the situation. Shortly after Conrad announced his wedding plans, two of the three archbishops died. The road was now clear for the marriage to take place. Isabella had her marriage to Humphrey annulled and Conrad became the king of Jerusalem. No one mentioned his two other wives.

The wedding reception took place in the Crusader camp. As the festivities progressed, a group of drunken knights decided to hold a jousting tournament outside the camp’s perimeter. As the knights made their way back to the camp, they were attacked and killed.

As the second winter of the siege set in, Conrad and Isabella retired to Tyre promising to send supplies and reinforcements – which never arrived. The ships returned to Europe, Saladin sent his forces home, to rest – and only the Crusaders, shivering and hungry, remained for another winter in the camp opposite the besieged city. Life in the Crusader camp during the winter of 1191 was harsh. Food for the soldiers and fodder for the horses ran out, and many began to have doubts that they would ever manage to take Acre, not to mention Jerusalem.

During the winter, part of the walls of Acre collapsed. The Crusaders launched an attack through the breach in the walls, and the garrison, mostly new troops, barely managed to stop the Crusaders from entering the city.

In September 1190, the two strongest European monarchs set out for the Holy Land. Richard sailed from Marseille and Phillip from Genoa. A few days later the two royal fleets met in Sicily, where things began to get complicated.

The king of Sicily, William II, was married to Richard’s sister Joan. On Richard’s arrival, William II died and his heir, Tancred, refused to return Joan’s dowry. At the same time, Richard canceled his engagement to Alice, Phillips half-sister, in order to wed Berengeria the daughter of the King of Navarre. The event did not improve the relations between the two kings.

After

Easter, the major forces of the Third Crusade finally began to arrive. Phillip

with six ships of the royal French fleet arrived on April 20, 1191, soon to be

joined by Conrad of Montferrat.

Phillip began immediately to reorganize the Crusader camp. The batteries and trenches were strengthened, new attack towers built, assault machines constructed, and fighting plans revised. On May 30, the Crusaders began to bombard the city and roll a “Welsh Cat” toward the “Accursed Tower”, the great tower at the northeastern corner of the walls. The Cat was a wooden tower with metal arms at its top that could tear out stones from the wall and dismantle it. Wet hides covered the towers to prevent the defenders on the walls to set them on fire. The Crusaders began to fill in the dry moat that surrounded the city while sappers dug under the walls in an attempt to topple them. The renewed activity raised morale in the Crusader camp.

The Muslim defenders hurled combustible firebombs at the towers and the attacking forces and sallied out from concealed posterns in the moat to thwart the attackers’ attempts to undermine the wall. The fighting continued around the clock until a portion of the wall collapsed and the Crusaders charged into the breach. For a short while, they managed to hold a bridgehead in the city. However, the Muslims counterattacked and the Crusaders retreated. That same night the Muslims shored up the wall.

Negotiations

After settling his sister’s dowry in Sicily, Richard set sail for the Holy Land. Three days out of Sicily the fleet ran into a storm and the ships dispersed. Several, including the one carrying Berengaria, took shelter in Cyprus. The Byzantine ruler of the island, Issac Commenus, on realizing the identity of the royal passenger, demanded a ransom for Berengaria’s release from the island. Richard was furious. Landing at Limassol on May 5, he conquered Cyprus, freed Berengaria, and wed her in the church in Famagusta. Leaving his new queen and her retinue in Cyprus, he continued to Acre.

Richard’s arrival in Acre, on June 8, 1191, rekindled the rivalry between Guy de Lusignan and Conrad of Montferrat. Guy, when he heard that Richard was in Cyprus, hurried to the island in order to get Richard’s support for his claim to the title of king of Jerusalem. Sibylla, Guy’s deceased wife, was Richard’s cousin and the Lusignan’s were vassals of the king of England. On his arrival, Richard announced that Guy was the legal heir to the title of King of Jerusalem. Conrad, enraged, left the Crusader camp and returned to Tyre.

Nine

days after Richard’s arrival in Acre, Phillip called for a Crusader attack.

Richard, claiming that the army was not ready, had the attack postponed. A few

days later Phillip again demanded to launch an attack, again Richard refused. Nevertheless,

Phillip decided to attack. The attack, beaten back by the Muslim defenders, was

a dismal failure.

Due

to the harsh living conditions in the camp, the two kings came down with a

fever. While they were recovering new ships with seasoned knights and soldiers

from Cyprus arrived. The bombardment of the walls and the constant firing of

arrows and lances at the defenders continued now all through the day and night.

As

the months dragged on the Acre garrison realized that the city’s fall was

inevitable, and sent out feelers to negotiate Acre’s surrender. The initial

Crusader demands were high. Richard wanted to continue fighting; Phillip

demanded the return of the Holy Land. The negotiations created a rift between

Richard and Phillip, and Saladin and his commanders in Acre.

On July 7, Saladin launched an attack on the Crusader camp. The attack failed and its purpose was unclear. That same night a powerful earthquake shook the Galilee. The Accursed Tower collapsed together with segments of the walls of the city. The defenders managed to patch up the damage, but it was clear that the game was over. 653 days had passed since the beginning of the siege and all sides were ready to bring it to an end.

On July 12, the Muslim leaders of Acre arrived at the Crusader camp to finalize the city’s capitulation. The Muslims agreed to deliver Acre to the Crusaders and return the Holy Cross captured at the Horns of Hattin. The Crusaders agreed to let the Muslims leave the city in peace with their families and possessions. Saladin agreed to release 2,000 Christian prisoners and pay the Crusader kings the enormous sum of 200,000 bezants. The treaty was brokered by Conrad of Montferrat, who had returned to Acre. For his efforts, he received 14,000 bezants.

Acre was handed over to the Crusaders and the royal banners raised over its walls. Once in possession of the city squabbling broke out over the spoils of war. The fighting orders, monasteries, and the Italian communes demanded their original property back. The communes demanded additional swaths of the city, for their efforts in transporting the Crusade to Acre. All of this angered the knights and soldiers who had done the actual fighting. Many returned home in disgust, including Phillip who announced his intentions of returning to France.

Apart from handing over the city, the other details of the agreement were not kept. Saladin did not have the funds to pay the two kings and demanded a number of installments. Once Saladin raised half the sum of the agreed payment, he demanded assurances that following the release of the Christian prisoners the Crusaders would release the Muslim garrison in the city.

The question as to who violated the agreement, the Christians or the Muslims, is a moot discussion. The release of Christian prisoners was erratic; the Holy Cross remained in Muslim hands, and the Crusaders did not release the Muslim garrison. At the beginning of August Richard was fed up with waiting. The entire Muslim garrison, with their families, were taken outside the city walls and slaughtered. The agreement was broken.

On August 23, Richard marched out of Acre to Jerusalem. In September, he won a brilliant victory at the Battle of Arsuf. Three days later, he conquered Jaffa. However, Jerusalem, the reason for the Crusade, remained in Muslim hands. On January 1192, Richard managed to see the towers of Jerusalem from the Hill of Nebi Samuel, northwest of the city. It was the nearest he got to the Holy city.

The Third Crusade was over. Richard and Saladin signed a three-year truce that left the coastal plain between Acre and Jaffa in the hands of the Crusaders. Before leaving the country, Richard, on the advice of his counselors, assigned the title of king of Jerusalem to Conrad of Montferrat. Guy de Lusignan received Cyprus.

On his way home, Richard was shipwrecked and fell into the hands of Duke Leopold of Austria. He spends the next three years as a prisoner of Leopold. Muslim killers, who penetrated the palace at Tyre disguised as monks, assassinated Conrad of Montferrat on April 28, 1192.

Crusader Acre flourished. It became the capital of the new Crusader kingdom of Jerusalem – a commercial hub between East and West, the headquarters of the Italian communal trading emporiums, the Crusader orders, and the great monasteries. It survived for one hundred years. In 1291, Acre was conquered by the Mameluke Sultan, al-Malik al-Ashraf Khalil ibn Kalaoun. After a short siege, the Muslim soldiers burst into the city and slaughtered anyone who did not manage to escape by sea. The sultan ordered the utter destruction of Acre so that it would never again serve as a bridgehead for a Christian return to the Holy Land. Acre remained an abandoned ruin for the next 300 years.