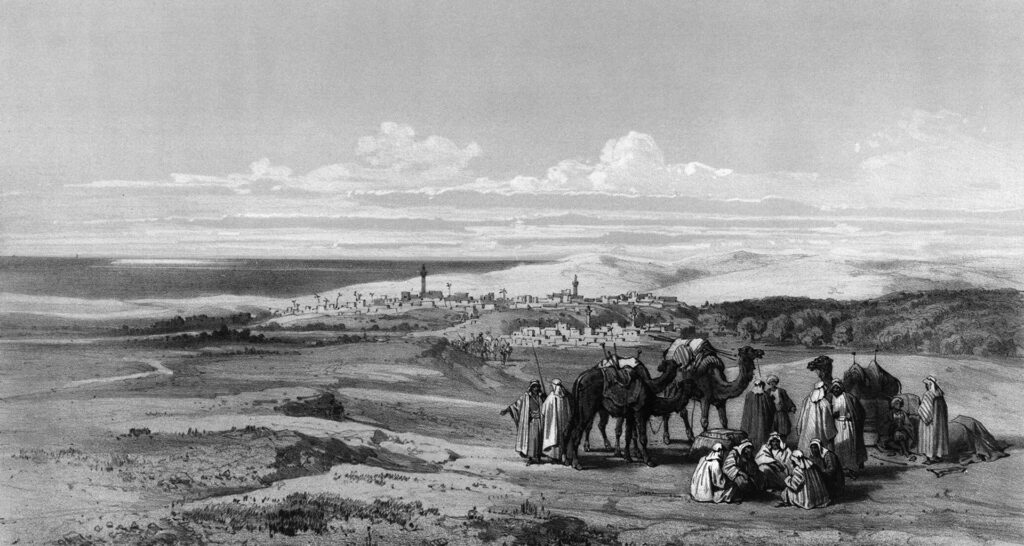

It is difficult to pinpoint when the Dead Sea and its historic sites were forgotten, but in the Middle Ages, major effort was required to visit the Dead Sea region, whose paths were unknown and its few places of settlement difficult to reach. In the early nineteenth century, when modern geographical research began, very few dared to travel to the Dead Sea. The Ottoman Empire, which had ruled this region since the sixteenth century, was in such disarray that, in 1831, the governor of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, gained control of the Land of Israel, holding it for nine years. The Bedouin tribes that roamed the deserts of the Middle East did not accept the overlordship of either the sultan in Istanbul or the Egyptian pasha in Cairo. Even if an adventurous explorer managed to obtain a permit from the sultan to visit a faraway corner of the empire such as the Dead Sea, the Bedouins showed no regard for this official sanction. At the very least, they demanded protection and passage money – each tribe in its own territory, according to the intertribal rivalries and wars over living space, grazing rights, and water sources.

It was impossible for a foreigner, especially a European, to just venture into the deserts of the Ottoman Empire. The first European travelers who attempted to navigate these routes learned to speak Arabic, versed themselves in Moslem customs, and dressed as Arabs, recording their impressions of this unknown world only when no prying eyes could watch. Some lost their lives in the attempt to explore these forbidden lands; they were murdered, died of unfamiliar diseases, lost their way, or dehydrated in the desert sun.

The first modern traveler to circumvent the Dead Sea was a German explorer, Ulrich Jasper Seetzen. Studying medicine in Gottingen, Germany (he became a doctor in 1789), Seetzen was exposed to a new approach in geography: employing travel observations and collections of flora, fauna, and artifacts to understand the world. It was one of his classmates, Alexander von Humboldt, the founder of modern geography, who developed the concept of travel in the field as the basis for the expansion of scientific knowledge. These new ideas profoundly influenced Seetzen; around 1799, he decided to devote himself to the discovery and research of the African continent. He lined up a few sponsors and contacted a few museums, promising to send them the specimens that he intended to collect during his travels. With the financial support for his mission secured, Seetzen set out for Africa, starting with Syria, which he reached in 1804. His first stop was Aleppo, where he improved his knowledge of Arabic and Moslem customs. In April 1805, he arrived in Damascus, from where he set out on a number of fact-finding trips to the Hauran and the Jordan Rift Valley. During his travels, he presented himself as a Moslem doctor by the name of Mousa al-Hakim (Mousa the doctor).

“I let my beard grow, dressed myself in a half-Turkish, half-Arab costume, took on an Arabic name, Mousa, and equipped myself with some medicines,” he reports.

The title of his second travel diary reveals the huge scope of his early travels: Travels from Aleppo to Damascus, and from there to the Hauran, the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon, the Leja, Hermon, Golan, al-Ghor, Jabel Ajlon, el Balaka, and around the Dead Sea to Mount Hermon and Jerusalem. Seetzen collected information obsessively. He wrote down the names of all the villages along his way that he did not manage to get to, made a list of all the riverbeds around the city of Kerak, copied over 150 Greek inscriptions that he encountered along the way, compiled a list of the types of Arabian race horses, meticulously recorded the mineral composition of rocks, mentioned the names of all the animals that he saw, and gathered countless samples of flora.

On April 9, 1807, Seetzen arrived at Saint Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai. He left behind a letter written in French, hanging it on the wall of the monastery’s guestroom: an amazing catalogue of unexplored sites that Seetzen was the first European to visit. Five years later, Swiss traveler John Lewis Burkhardt, the first European to reach Petra, copied it: “U. J. Seetzen, called Mousa, a German traveller, M.D. and recorder (Assesseur) of the College of H. M. the Emperor of all the Russias in the Seigneurie of Jever in Germany, came to visit the Convent of St. Catherine, the Mountains of Horeb, Moses and St. Catherine etc.; after having traversed all the ancient Eastern provinces of Palestine, namely: Batanea, Decapolis, Gileaditis, Ammonitis, Amorrhitis, and Moabitis, as far as the frontiers of Gebelene (Idumea) and after having twice made the tour of the Dead Sea, and having crossed the desert of Arabia Petraea, between the town of Hebron and Mt. Sinai, after a sojourn of ten days he continued his journey to the town of Suez” (Burkhardt, Travels in Syria and the Holy Land, 1822).

From Suez, Seetzen continued to Cairo. In March 1809, he sailed to Jidda in the Arabian Peninsula, bent on visiting the holy cities of Islam before continuing onward to the main area of his research: Africa. However, when he arrived in Mecca, he aroused the suspicions of the imam, who had him poisoned. Seetzen died in September 1811. His journals and notes were published 50 years later. When they finally were presented to the public, it turned out that they still were the most accurate descriptions of the areas he had visited. A sketch that Seetzen made of the Dead Sea area became the base for the first modern map of the Dead Sea.

Seetzen was not only the first modern explorer to circumvent the Dead Sea, but also the first to put Masada on the map, under the name “Szebby,” which was an Arabic distortion of the name “Saba,” that is, Masada.

A decade after Seetzen’s journey, two officers from the British Royal Navy, Charles Leonard Irby and James Mangles, set out on a brief tour of Europe and the Middle East. The tour that was planned to last for a few short months turned into a fascinating four-year adventure.

Following a comprehensive visit to the antiquities of Egypt, the two set out on camels to cross the Sinai desert to reach Jaffa. From there, they traveled north along the coast to Caesarea, Haifa, Acre, and Rosh Hanikra. They toured Lebanon; visited Tripoli, Homs, Aleppo, and Damascus; traveled through the Hauran and the Golan; descended to the Hula Valley; crossed the bridge of the Daughters of Jacob; visited Banias and the Hula Lake; ascended to Safed; passed through Tiberias, Zemah, Hamat Gader, and Beit She’an; and finally recrossed the Jordan to visit Jarash and Salt in Transjordan.

In May 1818, they planned to circumvent the Dead Sea and from there travel to Petra, in accordance with the wishes of their traveling companion and sponsor, Mr. Bankes. With typical English understatement, they explain the difficulties of undertaking this voyage: “as the only two Europeans who had ever been at… Petra [Seetzen and Burkhardt] are both dead…. performed this trip alone and in disguise… and made all their observations by stealth, which necessarily rendered their remarks very brief and cursory” (Charles Leonard Irby and James Mangles, Travels in Egypt and Nubia, Syria, and Asia Minor; During the Years 1817 & 1818). They decided to set out disguised as Moslems; Irby became Abdullah and Mangles, Hassan. After many difficulties, they finally made it to Petra. The return trip was around the southern edge of the Dead Sea, which resulted in a fascinating description of the vegetation and landscape of the Dead Sea shore and the fertile Zohar Valley.

While riding back to Jerusalem, they reported on a phenomena that baffled Dead Sea experts for many decades. As they descended from Kerak to the eastern shore of the Dead Sea, they encountered a small caravan of horses and mules on their way to Jerusalem. Irby and Mangles overtook the caravan and on reaching the shore of the Dead Sea, turned south in order to ride around the southern edge and come up again on the other (western) side. As they rode up the western side, they suddenly saw, in the distance, the small caravan walking in front of them. The caravan, they reported, had crossed the sea on a shallow ford in its center. This enigmatic ford never was seen again, but inspired much speculation. If it had existed, then it would have been one of the reasons for the location of Masada. This short cut across the Dead Sea is exactly opposite, and in full sight of, the fortress. It would have been the shortest route between the oasis of Ein Gedi along the western shores of the sea and the fertile plains around Kerak on the other side of the sea and the shortest route from Jerusalem to the Nabatean Kingdom.

Seventeen years passed before the next chapter in the rediscovery of the Dead Sea area: the sad sojourn on the sea of Christopher Costigan, who set out in a small boat with a Maltese servant to sail on the Dead Sea. The 25-year-old Irishman decided to sail down the Jordan River from the Sea of Galilee to the Dead Sea and continue to sail around its coast. Costigan bought a boat in Beirut, transferred it to Acre, and then transported it on camelback to the Sea of Galilee. He arrived there at the height of summer, in July 1835, but the Jordan, then a mighty river, still had a strong, turbulent current that overturned Costigan’s small boat repeatedly. He did not give up and instead hired camels to carry the boat to Jericho and the Dead Sea. A few days after he and his servant arrived in Jericho, he sailed the boat on the waters of the Dead Sea. For the next eight days, Costigan circumvented the shores, measuring the depth of the waters at different points. At night, he slept on shore. At four points along the shores, the two sailors saw ancient ruins, one of which they identified as the ruins of Gomorrah. On the sixth day of their voyage, they ran out of water. The next day, Costigan started to drink Dead Sea water and on the eighth day, they barely managed to get back to the northern shore. The Maltese servant set out to seek help and left Costigan on the beach lying under the boat, where a group of Bedouins discovered him and took him and the boat to Jericho. The Maltese, in the meantime, made it to Jerusalem, where he recruited the aid of an European missionary, John Nicolayson. The missionary rushed to Jericho and found Costigan completely dehydrated. After harnessing a makeshift stretcher for Costigan to a horse, the missionary managed to transport him to Jerusalem, where a doctor eventually revived him. By then, however, he had contracted malaria, which claimed his life a few days later. He was buried in Jerusalem, in the Protestant cemetery on Mount Zion.

Two years after Costigan’s tragic attempt to sail the Dead Sea, two additional Englishmen, G. H. Moore and W. G. Beke, set out to make trigonometric measures on the Dead Sea. The two bought a boat in Beirut, shipped it to Jaffa, and transported it to Jericho via Jerusalem. They only managed to complete some of the tasks that they took upon themselves because their Bedouin guides were scared of entering the territory of the hostile tribes around the sea. Even so, they made some interesting discoveries, finding that the boiling point of water is much higher than normal at the Dead Sea. This led them to the conclusion that the Dead Sea is substantially lower than sea level. Barometers already had been invented by then, but they were too cumbersome to take along to the desert. It was only in 1841 that the real level of the Dead Sea finally was measured in a series of horizontal measurements taken with a level. An officer of the British Royal Engineers, J. F. A. Symonds, spent 10 weeks measuring the difference in elevation between the Mediterranean Sea at Jaffa and Jerusalem and then went on to measure the difference in elevation between Jerusalem and the Dead Sea. His result – minus 1,311 feet, about 437 meters below sea level – was very close to the measurement that officers of the British Geographic Society obtained with a barometer a few decades later. Once that was solved, explorers moved on to the challenge of measuring the difference in height between the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea, which of course influenced the flow of the Jordan River, a topic which held their attention throughout the 1840s.

In 1847, Lt. Thomas Molyneux, of HMS Spartan, and three volunteers were sent to sail down the Jordan from the Sea of Galilee in order to measure the difference in elevation. None of the four had any experience with Bedouins or the desert. Molyneux set out at the end of August for Acre. From there, he transferred his boat on camelback to Tiberias, sailing from there into the Jordan River. Right from the beginning, Molyneux had trouble with the Bedouins. He refused to pay passage money and then insulted them by finally offering too meager a sum accompanied by a display of his arsenal of arms. Very soon, the four discovered that they could not continue on the serpentine river and so they continued on shore, where they discovered that they were amidst a large number of Bedouin encampments. Molyneux sent his companions to try to navigate the river again, but they were attacked by Bedouins who stole everything on board the boat. When the boat failed to arrive at the agreed-upon meeting point, Molyneux set out to look for his men, found the empty boat, and made a dash for Jericho and Jerusalem, where he put together a search party that was unable to find his crew.

Molyneux did not give up. He recruited a new crew: a guide from Tiberias and a young Greek from Jerusalem. As evening fell, he set sail on the Dead Sea. Molyneux’s boat was equipped with only two oars and his crew members did not have the faintest idea of how to maneuver the small vessel. After two stormy nights at sea, Molyneux realized that they would not make it to the peninsula in the middle of the eastern shore and decided to return to Jericho. After a night and a day of hard rowing, the three managed to return to the northern shore. Molyneux loaded the boat on camels and managed to return to the HMS Spartan, where he discovered his three original companions, safe and sound. They had managed to make their way back to the ship. Molyneux, like Costigan, came down with malaria, and died in November 1847, on board his ship in Tripoli or Beirut.